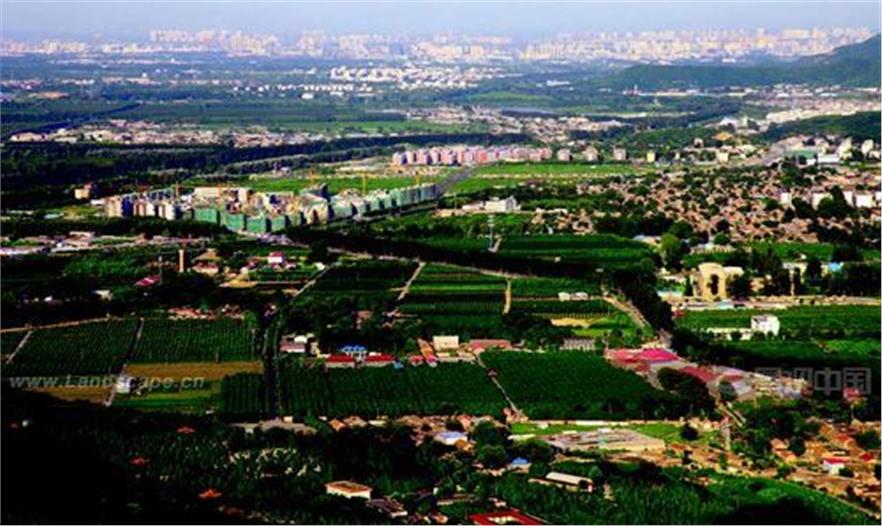

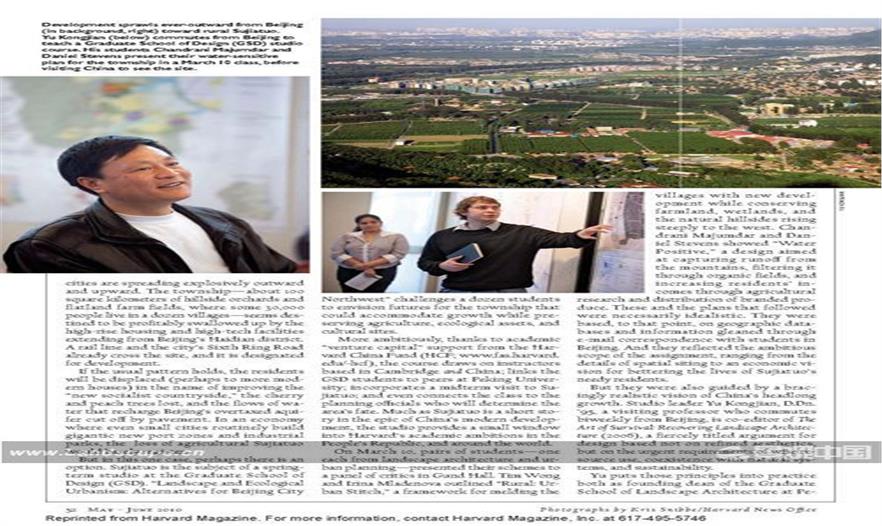

SUJIATUO TOWNSHIP, 30 kilometers northwest of central Beijing, lies directly in the path of the swiftest, most massive urbanization in human history. As incomes rise and tens of millions of people migrate from China’s countryside, dozens of dense cities are spreading explosively outward and upward. The township—about 100 square kilometers of hillside orchards and flatland farm fields, where some 30,000 people live in a dozen villages—seems destined to be profitably swallowed up by the high-rise housing and high-tech facilities extending from Beijing’s Haidian district.A rail line and the city’s Sixth Ring Road already cross the site, and it is designated for development.

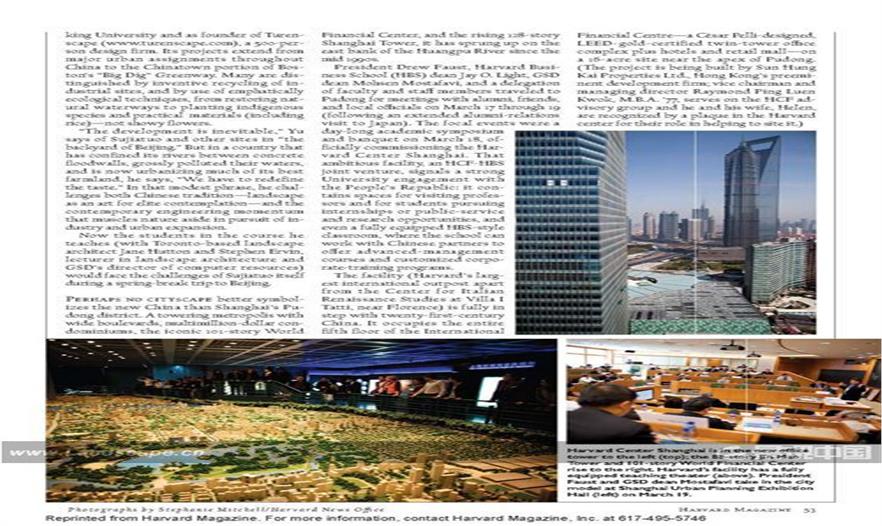

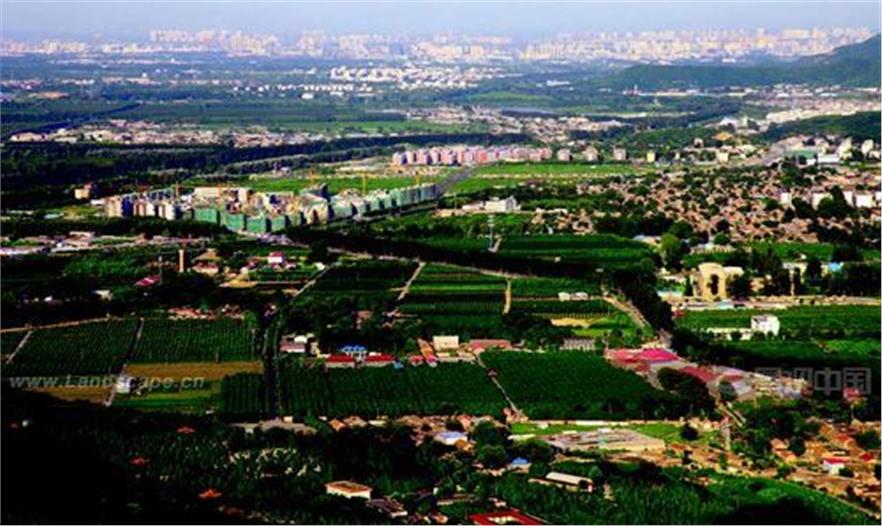

Development sprawls ever-outward from Beijing toward rural Sujiatuo.

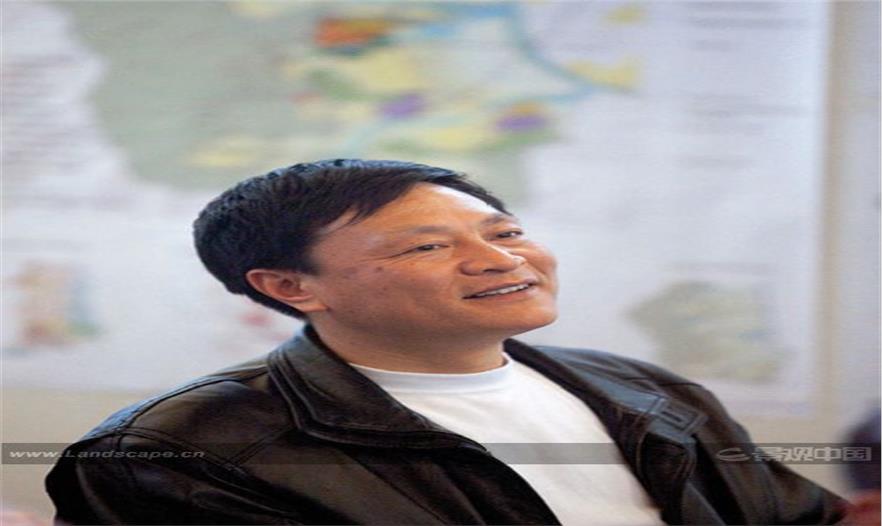

Yu Kongjian commutes from Beijing to teach a Graduate School of Design (GSD) studio course. His students Chandrani Majumdar and Daniel Stevens present their water-sensitive plan for the township in a March 10 class, before visiting China to see the site.

If the usual pattern holds, the residents will be displaced (perhaps to more modern houses) in the name of improving the “new socialist countryside,” the cherry and peach trees lost, and the flows of water that recharge Beijing’s overtaxed aquifer cut off by pavement. In an economy where even small cities routinely build gigantic new port zones and industrial parks, the loss of agricultural Sujiatuo would barely register.

But in this one case, perhaps there is an option. Sujiatuo is the subject of a springterm studio at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). “Landscape and Ecological Urbanism: Alternatives for Beijing City Northwest” challenges a dozen students to envision futures for the township that could accommodate growth while preserving agriculture, ecological assets, and cultural sites. More ambitiously, thanks to academic “venture capital” support from the Harvard China Fund (HCF; www.fas.harvard.edu/~hcf), the course draws on instructors based in Cambridge and China; links the GSD students to peers at Peking University; incorporates a midterm visit to Sujiatuo; and even connects the class to the planning officials who will determine the area’s fate. Much as Sujiatuo is a short story in the epic of China’s modern development, the studio provides a small window into Harvard’s academic ambitions in the People’s Republic, and around the world.

On March 10, pairs of students—one each from landscape architecture and urban planning—presented their schemes to a panel of critics in Gund Hall. Tim Wong and Irina Mladenova outlined “Rural: Urban Stitch,” a framework for melding the villages with new development while conserving farmland, wetlands, and the natural hillsides rising steeply to the west. Chandrani Majumdar and Daniel Stevens showed “Water Positive,” a design aimed at capturing runoff from the mountains, filtering it through organic fields, and increasing residents’ incomes through agricultural research and distribution of branded produce. These and the plans that followed were necessarily idealistic. They were based, to that point, on geographic databases and information gleaned through e-mail correspondence with students in Beijing. And they reflected the ambitious scope of the assignment, ranging from the details of spatial siting to an economic vision for bettering the lives of Sujiatuo’s needy residents.

But they were also guided by a bracingly realistic vision of China’s headlong growth. Studio leader Yu Kongjian, D.Dn. 95, a visiting professor who commutes biweekly from Beijing, is co-editor of The Art of Survival: Recovering Landscape Architecture (2006), a fiercely titled argument for design based not on refined aesthetics, but on the urgent requirements of wise resource use, coexistence with natural systems, and sustainability.

Yu puts those principles into practice both as founding dean of the Graduate School of Landscape Architecture at Pe- king University and as founder of Turenscape (www.turenscape.com), a 500-person design firm. Its projects extend from major urban assignments throughout China to the Chinatown portion of Boston’s “Big Dig” Greenway. Many are distinguished by inventive recycling of industrial sites, and by use of emphatically ecological techniques, from restoring natural waterways to planting indigenous species and practical materials (including rice)—not showy flowers.

“The development is inevitable,” Yu says of Sujiatuo and other sites in “the backyard of Beijing.” But in a country that has confined its rivers between concrete floodwalls, grossly polluted their waters, and is now urbanizing much of its best farmland, he says, “We have to redefine the taste.” In that modest phrase, he challenges both Chinese tradition—landscape as an art for elite contemplation—and the contemporary engineering momentum that muscles nature aside in pursuit of industry and urban expansion.

Now the students in the course he teaches (with Toronto-based landscape architect Jane Hutton and Stephen Ervin, lecturer in landscape architecture and GSD’s director of computer resources)

would face the challenges of Sujiatuo itself during a spring-break trip to Beijing.

Perhaps no cityscape better symbolizes the new China than Shanghai’s Pudong district. A towering metropolis with wide boulevards, multimillion-dollar condominiums, the iconic 101-story World Financial Center, and the rising 128-story Shanghai Tower, it has sprung up on the east bank of the Huangpu River since the mid 1990s.

President Drew Faust, Harvard Business School (HBS) dean Jay O. Light, GSD dean Mohsen Mostafavi, and a delegation of faculty and staff members traveled to Pudong for meetings with alumni, friends, and local officials on March 17 through 19 (following an extended alumni-relations visit to Japan). The focal events were a day-long academic symposium and banquet on March 18, officially commissioning the Harvard Center Shanghai. That ambitious facility, an HCF-HBS joint venture, signals a strong University engagement with the People’s Republic: it contains spaces for visiting professors and for students pursuing internships or public-service and research opportunities, and even a fully equipped HBS-style classroom, where the school can work with Chinese partners to offer advanced-management courses and customized corporate-training programs.

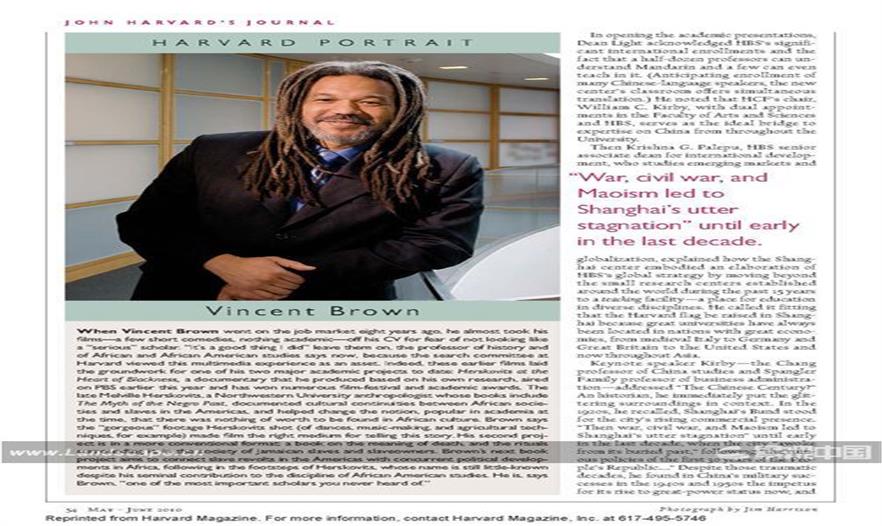

The facility (Harvard’s largest international outpost apart from the Center for Italian Renaissance Studies at Villa I Tatti, near Florence) is fully in step with twenty-first-century China. It occupies the entire fifth floor of the International Financial Centre—a César Pelli-designed, LEED-gold-certified twin-tower office complex plus hotels and retail mall—on a 16-acre site near the apex of Pudong. (The project is being built by Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd., Hong Kong’s preeminent development firm; vice chairman and managing director Raymond Ping Luen Kwok, M.B.A. ’77, serves on the HCF advisory group and he and his wife, Helen, are recognized by a plaque in the Harvard center for their role in helping to site it.)

Harvard Center Shanghai is in the new office tower to the left ; the 88-story Jin Mao Tower and 101-story World Financial Center rise to the right.

Harvard’s facility has a fully equipped teaching theater.

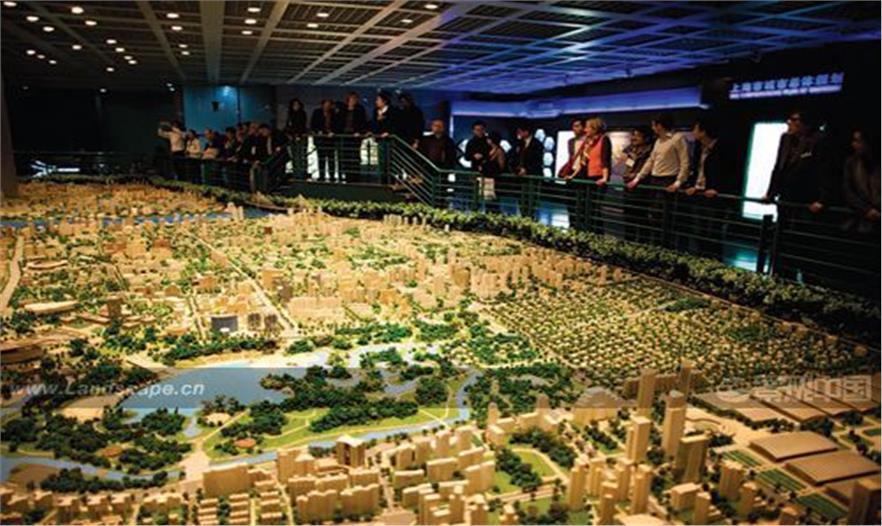

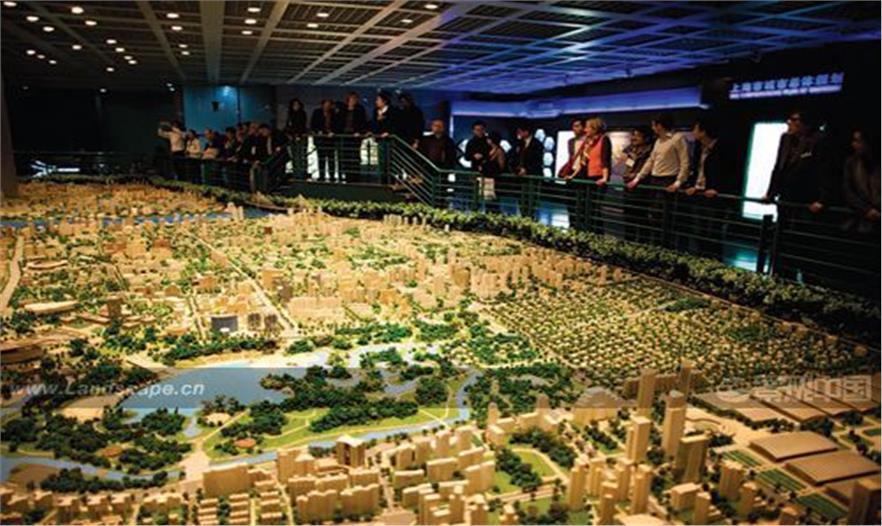

President Faust and GSD dean Mostafavi take in the city model at Shanghai Urban Planning Exhibition Hall on March 19.In opening the academic presentations, Dean Light acknowledged HBS’s significant international enrollments and the fact that a half-dozen professors can understand Mandarin and a few can even

teach in it. (Anticipating enrollment of many Chinese-language speakers, the new center’s classroom offers simultaneous translation.) He noted that HCF’s chair, William C. Kirby, with dual appointments in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and HBS, serves as the ideal bridge to expertise on China from throughout the University.

“War, civil war, and Maoism led to Shanghai’s utter stagnation” until early in the last decade.

Then Krishna G. Palepu, HBS senior associate dean for international development, who studies emerging markets andglobalization, explained how the Shanghai center embodied an elaboration of HBS’s global strategy by moving beyond the small research centers established around the world during the past 15 years to a teaching facility—a place for education in diverse disciplines. He called it fitting that the Harvard flag be raised in Shanghai because great universities have always been located in nations with great economies, from medieval Italy to Germany and Great Britain to the United States andnow throughout Asia.

Keynote speaker Kirby—the Chang professor of China studies and Spangler Family professor of business administration—addressed “The Chinese Century?” An historian, he immediately put the glittering surroundings in context. In the 1920s, he recalled, Shanghai’s Bund stood for the city’s rising commercial presence. “Then war, civil war, and Maoism led to Shanghai’s utter stagnation” until early in the last decade, when the city “awoke from its buried past,” following “the ruinous policies of the first 30 years of the People’s Republic….” Despite those traumatic decades, he found in China’s military successes in the 1940s and 1950s the impetus for its rise to great-power status now, and in its capitalist flowering at the beginning of the last century the roots of its new economic efflorescence.

Kirby reviewed the government’s success in building infrastructure and the dynamism of Chinese entrepreneurs. He highlighted the remarkable expansion of Chinese higher education—“a great and welcome challenge to American universities”—and raised the critical issue of academic governance: the degree of autonomy granted to institutions, public and private, to pursue their “broader public purpose” of educating leaders for the future—a mission, he said, that two “notquite-democratic institutions,” Harvard and China, pursue together.

Looking ahead, Kirby foresaw a century “for all of us, in a world of shared aspirations and common problems.” In the past, he said, “We used to say about the Chinese-American relationship, in so many areas, that we were tong chuang yi meng (sleeping in the same bed, while dreaming different dreams).…We are without question now, together, embedded in a global system of learning and teaching…from each other, as never before, and sharing many, if not all, of the same dreams” tangibly in the Harvard Center Shanghai.

One of Kirby’s themes—acknowledgement of China’s development, but frank recognition of past costs and continuing challenges—sounded throughout the day. In “Architecture and Urbanism,” GSD dean Mostafavi, as moderator, asked the panelists how India and China could cope with their “phenomenal processes of urbanization”—prompting expressions of concern about pell-mell construction of trophy skyscrapers without regard for livable community (evident in the immediate environs of Pudong) and about the loss of historic structures and farmland.

Carswell professor of East Asian languages and civilizations Peter K. Bol and professor of Chinese literature Tian Xiaofei asked, “Who Cares about Chinese Culture?”—i lluminating the ways American and Chinese cultures reveal their multiple and shifting meanings and applications when brought into contact with one another. Barry R. Bloom, past dean of the Harvard School of Public Health, and colleagues explored “China’s Newest Revolution: Health for All?” After noting that life expectancy had tripled during the past century, Bloom pointed out that the opening of China’s economy to market forces in 1978 had resulted in the wholesale shift of healthcare costs to private payments, with devastating effects on rural health, widening gaps in access as incomes diverged, and perverse incentives for doctors and hospitals that led to abuse and enormous overuse of drugs and other therapies. Health reforms announced in 2009 promise to correct many of these problems, he said. But corruption, weak regulation, and deep-seated social challenges—from inadequate care for the burgeoning aged population to persistently high rates of suicide and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases—may not prove easily tractable.

A bilingual welcome to a binational academic center.

At day’s end, Starr professor of international business administration David B. Yoffie, who chairs executive education at HBS, outlined the compelling technologies—from mobile to “cloud” computing—that he sees propelling growth. That same day, China Mobile reported adding 65 million subscribers in 2009, bringing its total to 522 million—half the country’s user base; Verizon and AT&T, the U.S. market leaders, each have about 85 million cellular customers overall.

A framed work of calligraphy in the Harvard Center’s lobby presents a passage by Gu Xiancheng, a leader of the Donglin movement of the early 1600s—reformists’ attempt to invoke Confucian moral tradition to improve life during the decline of the late Ming dynasty. As translated by Bol, the passage reads:

Use moral principles to take charge of profit-seeking. Use profit-seeking to assist moral principles. Combined to complete each other, they will form a single stream.

That seems a fitting exhortation as Harvard tries to apply both liberal arts and professional disciplines to research and learning in China—and to China itself, as it relies on an unfettered market to grow, while adapting values and customs to its people’s lives today.

These principles, applied in specific context during the panels on urban development, healthcare, and other topics, were explicitly the subject of the luncheon address. Bass professor of government Michael Sandel, whose course “Justice” has reached wide audiences in book and video versions, spoke on “The Moral Limits of Markets.” Whatever their differences, he said, both the United States and the People’s Republic face the predicaments arising during the past few decades as market thinking, institutions, and values have reached into spheres of life traditionally governed by nonmarket norms. But “markets are not mere mechanisms,” he claimed, and can taint the goods and social social practices they come to govern: he cited for-profit schools and prisons; the sale of organs and access to transplants; and, in China’s hospitals, the sale of appointments to be seen by a medical professional. “Markets leave their mark,” Sandel asserted: once a good or service is for sale, it is valued as a commodity, abstracted from moral or political considerations. During an era of “market triumphalism,” he said, people had drifted from “having a market economy to being a market society”—a transition that many have accepted without reflection, given markets’ power to organize valuable productive activity. It was a challenging message within the ballroom of the Pudong Shangri-la, an impeccable outpost of China’s foremost luxury hotel chain—itself a concept that would have been oxymoronic when Sandel began teaching political philosophy at Harvard in 1980.

In her evening address, President Faust built upon the details of Harvard’s history of educational involvement with China: some 250 Chinese earned Harvard degrees between 1909 and 1929, she noted, and more than 1,200 students and scholars from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan enrolled or visited last year; the law and medical schools have been active in China for a century; and Harvard experts now work with their Chinese academic peers and government officials on health policy, pollution control, and a wide array of arts and sciences.

More broadly, she said, “In a single decade, along with the world’s fastest growing economy, China has created the most rapid expansion of higher education in human history.” In that growth she saw “unimagined possibilities for understanding and discovery. It is a race that everyone wins.” Importantly, she stressed, those possibilities lie not only within the vital realms of applied and professional knowledge, but also in the sphere of “creative and critical thinking…unfold[ing] not from a fixed model or prescribed solutions, but from vivid debate and unorthodox thinking.”

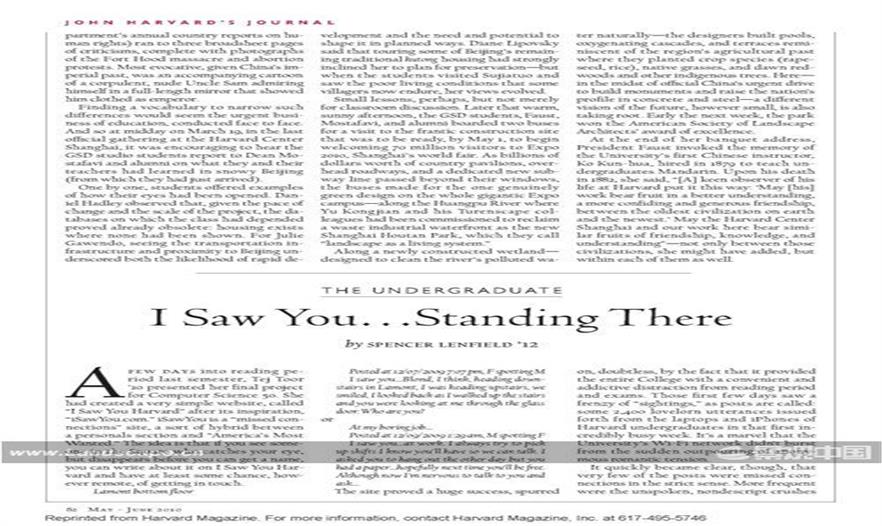

GSD students, alumni, and other Harvard guests tour the award-winning waterfront park at Shanghai’s Expo 2010 site (left)—an alternative, green model for development.

At the site, designer Yu Kongjian explains his vision to President Faust.

Faust illustrated that passion by citing journalist Theodore White’s recollections of his “swift passage from Harvard to China” as a first-year student in 1934. To escape the crowded Western Civ. Reading room in Boylston Hall, she said, White crossed the corridor to the empty Yenching Library; there, “bleary with reading about medieval trade, or the Reformation,” as he put it, he began to “pick Chinese volumes off the shelves—volumes on fine rice paper, blue-bound, bamboo-hooked volumes with strange characters,” until he himself became hooked and “I began to feel at home.”

In that era, East Asian studies was, as Faust put it, “a discipline centered on Chinese antiquities” of the sort that bewitched the young White. Today, the University offers more than 370 courses in the field—and students and scholars seemingly will need all of them to promote true understanding between the United States and China. In the week of the Harvard party’s visit, China Daily, which reflects government and Party views, was filled with furious critiques of American policy. “Politicizing yuan exchange can’t fix Sino-U.S. trade imbalance” read one op-ed—over a cartoon of a physician listening to the heart of an obese “U.S. Economy” figure and asking, “Is this the Chinese yuan, again?” An editorial on Google and Internet access said the issue had “become a tool in the hands of vested interests abroad to attack China under the pretext of Internet freedom”—“an absurdity…beyond comprehension and…intolerable.” An official report on “The Human Rights Record of the United States in 2009” (a response to the U.S. State De- partment’s annual country reports on human rights) ran to three broadsheet pages of criticisms, complete with photographs of the Fort Hood massacre and abortion protests. Most evocative, given China’s imperial past, was an accompanying cartoon of a corpulent, nude Uncle Sam admiring himself in a full-length mirror that showed him clothed as emperor.

Finding a vocabulary to narrow such differences would seem the urgent business of education, conducted face to face.And so at midday on March 19, in the last official gathering at the Harvard Center Shanghai, it was encouraging to hear the GSD studio students report to Dean Mostafavi and alumni on what they and their teachers had learned in snowy Beijing (from which they had just arrived).

One by one, students offered examples of how their eyes had been opened. Daniel Hadley observed that, given the pace of change and the scale of the project, the databases on which the class had depended proved already obsolete: housing exists where none had been shown. For Julie Gawendo, seeing the transportation infrastructure and proximity to Beijing underscored both the likelihood of rapid development and the need and potential to shape it in planned ways. Diane Lipovsky said that touring some of Beijing’s remaining traditional hutong housing had strongly inclined her to plan for preservation—but when the students visited Sujiatuo and saw the poor living conditions that some villagers now endure, her views evolved.

Small lessons, perhaps, but not merely for classroom discussion. Later that warm, sunny afternoon, the GSD students, Faust, Mostafavi, and alumni boarded two buses for a visit to the frantic construction site that was to be ready, by May 1, to begin welcoming 70 million visitors to Expo 2010, Shanghai’s world fair. As illions of dollars worth of country pavilions, overhead roadways, and a dedicated new subway line passed beyond their windows, the buses made for the one genuinely green design on the whole gigantic Expo campus—along the Huangpu River where Yu Kongjian and his Turenscape colleagues had been commissioned to reclaim a waste industrial waterfront as the new Shanghai Houtan Park, which they call “landscape as a living system.”

Along a newly constructed wetland—designed to clean the river’s polluted water naturally—the designers built pools, oxygenating cascades, and terraces reminiscent of the region’s agricultural past where they planted crop species (rapeseed, rice), native grasses, and dawn redwoods and other indigenous trees. Here—in the midst of official China’s urgent drive to build monuments and raise the nation’s profile in concrete and steel—a different vision of the future, however small, is also taking root. Early the next week, the park won the American Society of Landscape Architects’ award of excellence.

At the end of her banquet address, President Faust invoked the memory of the University’s first Chinese instructor, Ko Kun-hua, hired in 1879 to teach undergraduates Mandarin. Upon his death in 1882, she said, “[A] keen observer of his life at Harvard put it this way: ‘May [his] work bear fruit in a better understanding, a more confiding and generous friendship, between the oldest civilization on earth and the newest.’ May the Harvard Center Shanghai and our work here bear similar fruits of friendship, knowledge, and understanding”—not only between those civilizations, she might have added, but within each of them as well.

京公海網安備 110108000058號

京公海網安備 110108000058號